At an Innocence Project dinner, Peggy Sanders danced with Dennis Fritz, who was sent to prison for her daughter’s murder.

At an Innocence Project dinner, Peggy Sanders danced with Dennis Fritz, who was sent to prison for her daughter’s murder.In the Face of Great Loss, Embracing Innocence

By JIM DWYER

Published:New York Times May 10, 2008

The woman was seated just two chairs away at the table, but the man had to speak over music that filled the room.

At an Innocence Project dinner, Peggy Sanders danced with Dennis Fritz, who was sent to prison for her daughter’s murder.

“Peggy,” he said.

For a minute, Peggy Sanders did not hear her name being called. She is 65 and was visiting New York this week for the first time from a small town in Oklahoma to attend a big benefit dinner.

As a young virtuoso played piano, Ms. Sanders swayed slightly in her chair.

“Peggy,” the man said.

She glanced up.

“Want to dance?” he asked.

She giggled, the way an aunt might at a rambunctious nephew who tries to coax her onto the dance floor at a wedding. But she did not take his question seriously. Of the 600 people at the dinner, no one else made a move to dance: The chair backs had just inches of clearance.

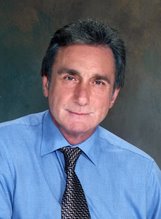

Even so, the man who asked the question, Dennis Fritz, needed no more encouragement. He edged around the table and took her hand. The floor may have been crowded, but the stage was wide open. He led her to the stairs. She climbed up, a crown of white hair over her smile. Mr. Fritz wore jeans and a sport coat.

She lifted her hands and put them on his back and shoulder. They drifted together and gently twirled, a dance salvaged from a trail of wreckage that stretches back to 1982.

Peggy Sanders first saw Dennis Fritz 21 years ago, wearing an orange jail jumpsuit as he was brought into the courthouse in Ada, Okla., to face charges that he had murdered Ms. Sanders’s daughter Debbie Carter. She was 21, a waitress who had just gotten her own apartment, when she was killed in December 1982.

“I hated him so bad,” Ms. Sanders said. “Why did they do that to my little girl?”

Mr. Fritz, a high school science teacher, was spared the death penalty by one vote and got life without parole. A co-defendant, Ron Williamson, once a star pitching prospect, was sentenced to die. He came within five days of execution.

Neither man had anything to do with the crime: They were convicted on the word of jailhouse snitches who bartered their stories for sweetheart plea deals and by pseudoscientific testimony that falsely linked them to 17 hairs found at the crime scene. In 1999, lawyers in Oklahoma and with the Innocence Project in New York arranged DNA tests that cleared Mr. Fritz and Mr. Williamson. The tests implicated another man, whose DNA was matched to the hair and semen found on the victim’s body.

“They were railroaded,” Ms. Sanders said. The other man is now serving a life sentence for the murder.

Ms. Sanders saw it plain. All around her, though, people refused to rewrite the ending to her daughter’s murder, clinging to the belief that Mr. Fritz and Mr. Williamson somehow had been part of the killing, a spurning of reality so common that it has practically become an epidemic as DNA tests, year in and out, clear the wrongfully convicted.

The elders of Mr. Williamson’s family church refused to let the two men use the hall for a press conference after their release. The Williamson family received threatening calls. Their pastor pointedly did not acknowledge Mr. Williamson from the pulpit when he came for his first church service after leaving prison.

Then Mr. Williamson, a high school baseball star drafted in the second round in 1971 by the Oakland Athletics, made a call to Ms. Sanders.

“He said, ‘This is Ron Williamson; I did not kill your daughter,’ ” Ms. Sanders recalled. “I said, ‘I know, hon.’ ”

Ms. Sanders, who married as a teenager and quickly had three children, struggled for years after the murder of Debbie. Yet she embraced Mr. Williamson, Mr. Fritz and their families after the men were exonerated.

“I had to do it for my daughter,” she said. “They had become victims of this, too. People still don’t believe they’re innocent. I was just at a funeral, and a woman come up to me and said, ‘I know them two done it.’ I said, ‘No, they didn’t.’ ”

Mr. Williamson, who suffered from psychiatric problems, died in 2004. He is the subject of John Grisham’s book “The Innocent Man.” Mr. Fritz, 58, now lives in Missouri, and has also written a book, “Journey Toward Justice.” Christy Sheppard, a cousin of the murder victim, has become an advocate for the establishment of commissions to look into wrongful convictions.

All of them — the family of Debbie Carter, the family of Mr. Williamson, Mr. Grisham and Mr. Fritz — sat at one table Thursday evening for a dinner benefiting the Innocence Project.

Until an impulse hit Dennis Fritz, and he led his friend Peggy Sanders onto the stage, and they danced where everyone could see them.

No comments:

Post a Comment