From left, Josh Kezer of Columbia applauds as Dennis Fritz greets Darryl Burton as the former inmates told their stories of wrongful imprisonment as part of a Midwestern Innocence Project fundraiser Wednesday night in Neff Hall Auditorium at the University of Missouri.

Photo by Parker Eshelman

Josh Kezer speaks to audiences across the county warning of the reality of wrongful convictions. He doesn’t do it for himself or the publicity; he passionately tells his tale for all the men and women he believes deserve a new day in court.

In front of a standing-room-only classroom last night on the University of Missouri campus, Kezer and two other exonerated inmates told their stories in an effort to raise money for the Midwestern Innocence Project. Through fundraising, the organization provides legal counsel for prison inmates in cases that have a high probability of being overturned.

Sean O’Brien, an associate professor at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law and Midwestern Innocence Project board member, is one of many masterminds who head exoneration cases or work to find an attorney to handle a case. With a staff of two attorneys, a fundraiser, legal secretary and several volunteers in Kansas City, he works to conduct the groundwork needed to jump-start a potential exoneration case.

“We want people to be able to put a face on the issue,” O’Brien said. “People understand there are innocent people in prison, but this makes it real to them.”

O’Brien and project attorneys rely on volunteers to sort through the 700 cases the project has on file. Only two or three cases will be selected this year, he said, sometimes making a successful exoneration into a five-year process.

DNA evidence and testing technologies have contributed to clearing numerous inmates nationwide, including 20 Missouri cases since 1980. Typical components of an exoneration case include eyewitness misidentification, junk science, false confessions, lousy lawyering and snitch testimony, O’Brien said. Each of the three exonerated speakers’ cases was a mixed bag of such components, including snitch testimony.

Kezer was 17 when he was arrested for shooting a Southeastern Missouri State University student three times. He was prosecuted in Scott County and served 16 years in state prison. He was exonerated last February after a rebuke of prosecutor-turned-Congressman Kenny Hulshof.

In a 44-page decision, a Cole County circuit judge said Hulshof withheld key evidence from defense attorneys and embellished details in his closing arguments. Conflicting testimony and three jail inmates who had claimed Kezer confessed to the killing later acknowledged they lied in hopes of getting reduced sentences.

“They didn’t care about the truth. I should have never been arrested,” Kezer said. “That’s not me saying that. That’s out of the judge’s mouth.”

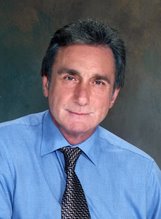

Also sharing his story was former high school science teacher Dennis Fritz. Ron Williamson and Fritz were convicted in the sexual assault and murder of a 21-year-old woman who was found strangled in December 1982 in Ada, Okla. In 1988, both men were convicted, partially because of microscopic hair comparisons done as part of a scientific testing method that has since been largely discredited.

Fritz and Williamson, who served 11 years in prison, also were convicted based on testimony by witness Glen Gore, an informant later shown by DNA testing to have been the real killer. Gore was later convicted of rape and murder.

“I was convicted by snitch testimony,” Fritz said. “These were the dirtiest of the dirty and the lousiest of the lousy. They needed to find me guilty.”

Fritz’s tale became the subject of a John Grisham book, “The Innocent Man.”

St. Louis resident Darryl Burton served the longest time in prison of the three speakers. For 24 years, he worked to clear his name of a murder he did not commit. He said he found faith and his grown-up daughter in the process.

Burton was convicted in 1985 of a gas station murder on the basis of testimony by two people claiming to be witnesses. No physical evidence or motive was offered at the trial, but the two witnesses made deals with the prosecutor in exchange for their testimony because they faced unrelated felony charges.

“I thought it would take 24 hours for them to realize they made a mistake and let me go,” Burton said. “It took 24 years.”

By Brennan David

Thursday, February 4, 2010

No comments:

Post a Comment