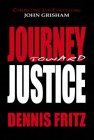

As I was researching the pros and cons abouth the Death Penalty, I came across this in The Congressional Record.For people who are visiting my blog for the first time. I decided after reading the book Journey Toward Justice, Author Dennis Fritz, to join his Journey Toward Justice. I started this blog to bring about Public Awareness of major issues in his book. This is one of them. I do wish Dennis Fritz a Wonderful Journey in his Journey Toward Justice. He was in prison for a unwarranted prosecution and wrongful conviction and spent 12 tortuous years in prison as a innocent man. Please pass my blog along and join My Journey.

Here is what I read: Since it is from The Congressional Record I can Post the entire text.

[Page: S198]

Mr. LEAHY. Mr. President, I wish to call attention to a growing national crisis in the administration of capital punishment. People of good conscience can and will disagree on the morality of the death penalty. But I am confident that we should all be able to agree that a system that may sentence one innocent person to death for every seven it executes has no place in a civilized society, much less in 21st century America. But that is what the American system of capital punishment has done for the last 24 years.

A total of 610 people have been executed since the reinstatement of capital punishment in 1976. During the same time, according to the Death Penalty Information Center, 85 people have been found innocent and were released from death row. These are not reversals of sentences, or even convictions on technical legal grounds; these are people whose convictions have been overturned after years of confinement on death row because it was discovered they were not guilty. Even though in some instances they came within hours of being executed, it was eventually determined that, whoops, we made a mistake; we have the wrong person.

What does this mean? It means that for every seven executions, one person has been wrongly convicted. It means that we could have more than three innocent people sentenced to death each year. The phenomenon is not confined to just a few States; the many exonerations since 1976 span more than 20 different States. And of those who are found innocent--not released because of a technicality, but actually found innocent--what is the average time they spent on death row, knowing they could be executed at any time? What is the average time they spent on death row before somebody said, we have the wrong person? Seven and a half years.

This would be disturbing enough if the eventual exonerations of these death row inmates were the product of reliable and consistent checks in our legal system, if we could say as Americans, all right, you may spend 7 1/2 years on death row, but at least you have the comfort of knowing that we are going to find out you are innocent before we execute you. It might be comprehensible, though not acceptable, if we as a society lacked effective and relatively inexpensive means to make capital punishment more reliable. But many of the exonerated owe their lives to fortuity and private heroism, having been denied commonsense procedural rights and inexpensive modern scientific testing opportunities--leaving open the very real possibility that there have been a number of innocent people executed over the last few decades who were not so fortunate.

Let me give you a case. Randall Dale Adams. Here is a man who might have been routinely executed had his case not attracted the attention of a filmmaker, Earl Morris. His movie, `The Thin Blue Line,' shredded the prosecution's case and cast a national spotlight on Adams' innocence.

Consider the case of Anthony Porter. Porter spent 16 years on death row. That is more years than most Members of the Senate have served. He spent 16 years on death row. He came within 48 hours of being executed in 1998, but he was cleared the following year. Was he cleared by the State? No. He was cleared by a class of undergraduate journalism students at Northwestern University, who took on his case as a class project. That got him out. Then the State acknowledged that it had the wrong person, that Porter had been innocent all along. He came within 48 hours of being executed, and he would have been executed had not this journalism class decided to investigate his case instead of doing something else. Now consider the cases of the unknown and the unlucky, about whom we may never hear.

Last year, former Florida Supreme Court Justice Gerald Kogan said he had `no question' that `we certainly have, in the past, executed . . . people who either didn't fit the criteria for execution in the State of Florida, or who, in fact, were, factually, not guilty of the crime for which they have been executed.' This is not some pie-in-the-sky theory. Justice Kogan was a homicide detective and a prosecutor before eventually rising to Chief Justice.

This crisis has led the American Bar Association and a growing number of State legislators to call for a moratorium on executions until the death penalty can be administered with less risk to the innocent. This week, the Republican Governor of Illinois, George Ryan, announced he plans to block executions in that State until an inquiry has been conducted into why more death row inmates have been exonerated than executed since 1977 when Illinois reinstated capital punishment. Think of that. More death row inmates exonerated than executed.

Governor Ryan is someone who supports the death penalty. But I agree with him in bringing this halt. He said: `There is a flaw in the system, without question, and it needs to be studied.' The Governor is absolutely right. I rise to bring to this body the debate over how we as a nation can begin to reduce the risk of killing the innocent.

I hope that nobody of good faith--whether they are for or against the death penalty--will deny the existence of a serious crisis. Sentencing innocent women and men to death anywhere in our country shatters America's image in the international community. At the very least, it undermines our leadership in the struggle for human rights. But, more importantly, the individual and collective conscience of decent Americans is deeply offended and the faith in the working of our criminal justice system is severely damaged. So the question we should debate is, What should be done?

Some will be tempted to rely on the States. The U.S. Supreme Court often defers to `the laboratory of the States' to figure out how to protect criminal defendants. After 24 years, let's take a look at that lab report.

As I already mentioned, Illinois has now had more inmates released from death row than executed since the death penalty was reinstated. There have been 12 executions, and 13 times they have said: Whoops, sorry. Don't pull the switch. We have the wrong person. This has happened four times in the last year alone.

In Texas, the State that leads the Nation in executions, courts have upheld death sentences in at least three cases in which the defense lawyers slept through substantial portions of the trial. The Texas courts said that the defendants in these cases had adequate counsel. Adequate counsel? Would any one of us if we were in a taxicab say we had an adequate driver who was asleep at the wheel? What we are saying is with a person's life at stake the defense lawyer slept through the trial, and the Texas courts say that is pretty adequate.

Meanwhile, in the past few years, the States have followed the Federal lead in expanding their defective capital punishment systems, curtailing appeal and habeas corpus rights, and slashing funding for indigent defense services. The crisis can only get worse.

The States have had decades to fix their capital punishment systems, yet the best they have managed is a system fraught with arbitrariness and error--a system where innocent people are sentenced to death on a regular basis, and it is left not to the courts, not to the States, not to the Federal Government, but to filmmakers and college undergraduates to correct the mistakes. History shows that we cannot rely on local politics to implement our national conscience on such fundamental points as the execution of the innocent.

What about the Supreme Court? In a 1993 case, it could not even make up its mind whether the execution of an innocent person would be unconstitutional. Do a referendum on that one throughout the Nation. Ask people in this Nation of a quarter billion people whether they think executing an innocent person should be considered constitutional or unconstitutional. Most in this country have no doubt that it would be unconstitutional, but that really does not matter: executing an innocent person is abhorrent--it is morally wrong. Whether you support the death penalty or not, executing an innocent person is wrong, and we in this body have the moral duty to express and implement America's conscience. We should be the Nation's conscience. The buck should stop in this Chamber where it always stops in times of national crisis.

How do we begin to stem the crisis? I have been posing this question to experts across the country for nearly a year. There is a lot of consensus over what must be done. In the next few weeks, I will introduce legislation that will address some of the most urgent problems in the administration of capital punishment.

Two problems in particular require our immediate attention. First, we need to ensure that defendants in capital cases receive competent legal representation at every stage in their case. Second, we have to guarantee an effective forum for death row inmates who may be able to prove their innocence.

In our adversarial system of justice, effective assistance of counsel is essential to the fair administration of justice. It is the principal bulwark against wrongful conviction.

I know this from my own experience as a prosecutor. It is the best way to reduce the risk that a trial will be infected by constitutional error, resulting in reversal, retrial, cost, delay, and repeated ordeals for the victim's family. Most prosecutors will tell you they would much prefer to have good counsel on the other side because there is less apt to be mistakes, there is less apt to be reversible error, and there is far more of a chance that you end up with the right decision.

Most defendants who face capital charges are represented by court-appointed lawyers. Unfortunately, the manner in which defense lawyers are selected and compensated in death penalty cases frequently fails to protect the defendant's rights. Some States relegate these cases to grossly unqualified lawyers willing to settle for meager fees. While the Federal Government pays defense counsel $125 an hour for death penalty work, the hourly rate in many States is $50 or less, and some States place an arbitrary and usually unrealistically low cap on the total amount a court-appointed attorney can bill.

New York recently slashed pay for counsel in capital cases by as much as 50 percent. They might say they are getting their money's worth if they cut out all the money for defense counsel. The conviction rate is probably going to shoot up. Let me tell you what else will go up--the number of innocent people who will be put to death.

Congress has done its part to make a bad situation worse. In 1996, Congress defunded the death penalty resource centers. This has sharply increased the chances that innocent persons will be executed.

You get what you pay for. Those who are on death row have found their lives placed in the hands of lawyers who are drunk during the trial--in some instances, lawyers who never bothered to meet their client before the trial; lawyers who never bothered to read the State death penalty statute; lawyers who were just out of law school and never handled a criminal case; and lawyers who were literally asleep on the job.

Even some of our best lawyers, diligent, experienced litigators, can do little when they lack funds for investigators, experts, or scientific testing that could establish their client's innocence. Attorneys appointed to represent capital defendants often cannot recoup even their out-of-pocket expenses. They are effectively required to work at minimum wag or below while funding their client's defense out of their own pockets.

Although the States are required to provide criminal defendants with qualified legal counsel, those who have been saved from death row and found innocent were often convicted because of attorney error. They might not have had postconviction review because their lawyer failed to meet a filing deadline. An attorney misses a deadline by even 1 day, and his death row client may pay the price with his life.

Let me be clear what I am talking about. I am not suggesting that there is a universal right to Johnnie Cochran's services. The O.J. Simpson case has absolutely nothing to do with the typical capital case, in which one or possibly two underfunded and underprepared lawyers try to cobble together a defense with little or no scientific or expert evidence and the whole process takes less than a week. These are two extremes. You go from the Simpson case, where the judge let the whole thing get out of control and we had a year-long spectacle, to the typical death penalty case which is rushed through without preparation in a matter of days. Somewhere there must be a middle ground.

Let me give three examples of some of the worst things that have happened--but not untypical.

Ronald Keith Williamson. In 1997, a Federal appeals court overturned Williamson's conviction on the basis of ineffectiveness of counsel. The court noted that the lawyer, who had been paid a total of $3,200 for the defense, had failed to investigate and present a fact to the jury. What was that fact? Somebody else confessed to the crime. If I were the defense attorney, I think one of the things that I would want to bring to the jury is the fact that somebody else confessed to the crime; Williamson's lawyer did not bother. Then, two years after the appeals court decision, DNA testing ruled out Williamson as the killer and implicated another man--a convicted kidnapper who had testified against Williamson at trial. Of course, he did. He is the one who committed the crime.

Let's next consider George McFarland. According to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, McFarland's lawyer slept through much of his 1992 trial. He objected to hardly anything the prosecution did. Here is how the Houston Chronicle described what happened as McFarland stood on trial for his life. This is not for shoplifting. He is on trial for his life.

Let me quote from the Houston Chronicle:

[Page: S199]

Seated beside his client . . . defense attorney John Benn spent much of Thursday afternoon's trial in apparent deep sleep. His mouth kept falling open and his head lolled back on his shoulders, and then he awakened just long enough to catch himself and sit upright. Then it happened again. And again. And again.

Every time he opened his eyes, a different prosecution witness was on the stand describing another aspect of the Nov. 19, 1991, arrest of George McFarland in the robbery-killing of grocer Kenneth Kwan.

When state District Judge Doug Shaver finally called a recess, Benn was asked if he truly had fallen asleep during a capital murder trial. `It's boring,' the 72-year-old longtime Houston lawyer explained. . . . Court observers said Benn seems to have slept his way through virtually the entire trial.

Unfortunately for McFarland, Texas' highest criminal court, several of whose members were coming up for reelection, concluded that this constituted effective criminal representation.

I guess they felt because the lawyer was in the courtroom, even though sound asleep, that would be effective representation. If you read the decision they probably would have ruled the same way if he had been at home sound asleep, so long as he had been appointed at some time.

McFarland is still on death row for a murder he insists he did not commit, on the basis of evidence widely reported by independent observers to be weak.

Then we have Reginald Powell, a borderline mentally retarded man who was 18 at the time of the crime. Mr. Powell was eventually executed. Why? Because he accepted his lawyer's advice to reject a plea bargain that would have saved his life.

There were a number of attorney errors at the trial. The advice he received seems to be very bad advice. Some may feel this advice, the advice given to this 18-year-old mentally retarded man, was affected by the flagrantly unprofessional conduct of the attorney, a woman twice Powell's age, who conducted a secret jailhouse sexual relationship with him during the trial. Despite this obvious attorney conflict of interest, Powell's execution went ahead in Missouri a year ago.

I ask each Member of the Senate when you go home tonight, or when you talk to your constituents, and when you consider the bill I will be introducing, to remember these cases and consult your conscience to ask whether these examples represent the best of 21st century American justice.

The judge who presided over McFarland's trial summed up the Texas court's view of the law quite accurately when he reasoned that, while the Constitution requires a defendant to be represented by a lawyer, it `doesn't say the lawyer has to be awake.' If your conscience says otherwise, maybe we ought to do something.

My proposal rests on a simple premise: States that choose to impose capital punishment must be prepared to foot the bill. They should not be permitted to tip the scales of justice by denying capital defendants competent legal services. We have to do everything we can to ensure the States are meeting their constitutional obligations with respect to capital representation.

Can miscarriages of justice happen when defendants receive adequate representation? Yes, they can still happen. So I think it is critical to ensure that death row inmates have a meaningful opportunity--not a fanciful opportunity but a meaningful opportunity--to raise claims of innocence based on newly discovered evidence, especially if it is evidence that is derived from scientific tests not available at the time of the trial.

Perhaps more than any other development, improvements in DNA testing have exposed the fallibility of the legal system. In the last decades, scores of wrongfully convicted people have been released from prison--including many from death row--after DNA testing proved they could not have committed the crimes for which they were convicted. In some cases the same DNA testing that vindicated the innocent helped catch the guilty.

Most recently, DNA testing exonerated Ronald Jones. He spent close to 8 years on death row for a 1985 rape and murder that he did not commit. Illinois prosecutors dropped the charges against Jones on May 18, 1999, after DNA evidence from the crime scene excluded him as a possible suspect. It was also DNA testing that eventually saved Ronald Keith Williamson's life, as I discussed earlier. He spent 12 years as an innocent man on Oklahoma's death row.

Can you imagine how any one of us would feel, day after day for 12 years, never knowing if we were just a few hours or a few days from execution, locked up on death row for a crime we did not commit?

Some of the major hurdles to postconviction DNA testing are laws prohibiting introduction of new evidence--laws that have tightened as death penalty supporters have tried to speed executions by limiting appeals. Only two States, New York and Illinois, require the opportunity for inmates to require DNA testing where it could result in new evidence of innocence. Elsewhere, inmates may try to get DNA evidence for years, only to be shut out by courts and prosecutors.

What possible reason could there be to deny inmates the opportunity to prove their innocence--and perhaps even help identify the real culprits--through new technologies? DNA testing is relatively inexpensive. But no matter what it costs, it is a tiny price to pay to make sure you have the right person.

The National Commission on the Future of DNA Evidence, a Federal panel established by the Justice Department and comprised of law enforcement, judicial, and scientific experts, issued a report last year urging prosecutors to consent to postconviction DNA testing, or retesting, in appropriate cases, especially if the results could exonerate the defendant.

In 1994, we set up a funding program to improve the quality and availability of DNA analysis for law enforcement identification purposes. The Justice Department has handed out tens of millions of dollars to States under this program. Last year alone, we appropriated another $30 million for DNA-related grants to States. That is an appropriate use of Federal funds. But we should not pass up the promise of truth and justice for both sides of our adversarial system that DNA evidence holds out. We at least ought to require that both sides have it available.

By reexamining capital punishment in light of recent exonerations, we can reduce the risk that people will be executed for crimes they did not commit and increase the probability that the guilty will be brought to justice. We can also help to make sure the death penalty is not imposed out of ignorance or prejudice.

I learned, first as a defense attorney and then as a prosecutor, that the pursuit of justice obliges us not only to convict the guilty, but also to exonerate the wrongly accused and convicted. That obligation is all the more urgent when the death penalty is involved.

Let's not have the situation where, today in America, it is better to be rich and guilty than poor and innocent. That is not equal justice. That is not what our country stands for.

I was proud to be a defense attorney. I was very proud to be a prosecutor. I have often said it was probably the best job I ever had. But there was one thought I always had every day that I was a prosecutor. I would look at the evidence over and over again and I would ask myself, not can I get a conviction on this charge, but will I be convicting the right person. I had cases where I knew I could get a conviction, but I believed we had the wrong person, and I would not bring the charge. I think most prosecutors feel that way. But sometimes in the passion of a highly publicized, horrendous murder, we can move too fast.

I urge Senators on both sides of the aisle, both those who support the death penalty and those who oppose it, to join in seeking ways to reduce the risk of mistaken executions.

Mr. President, I suggest the absence of a quorum.

The PRESIDING OFFICER. The clerk will call the roll.

The assistant legislative clerk proceeded to call the roll.

[Page: S200]

Mr. SMITH of New Hampshire. Mr. President, I ask unanimous consent that the order for the quorum call be rescinded.

The PRESIDING OFFICER. Without objection, it is so ordered.

END

The Growing Crisis In The Adminstration Of Capital Punishment

Senate - February 01,2000

Friday, March 30, 2007

The Growing Crisis In The Adminstration Of Capital Punishment

Labels:

article,

capital punishment,

death penalty,

Dennis Fritz,

news,

pros and cons,

Ron Williamson,

senate

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment