It took more than 11 years for Kansas City’s Dennis Fritz to be proven innocent of a murder he didn’t commit and released from an Oklahoma prison.

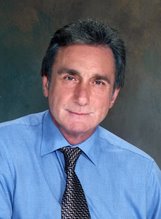

Dennis Fritz (left) and Ron Williamson upon their release from an Oklahoma prison in 1999.

Dennis Fritz author of "Journey Toward Justice"Dennis Fritz (left) and Ron Williamson upon their release from an Oklahoma prison in 1999.

It took three more years and the help of Kansas City attorney and MIP Board member Cheryl Pilate to obtain the compensation which Fritz and fellow exoneree Ron Williamson deserved for their wrongful convictions and years of incarceration. Fritz and Williamson were arrested, tried and convicted in the sexual assault and murder of 21-year old Debra Sue Carter, who was found strangled in December 1982 in Ada, Oklahoma.

In 1988, Fritz and Williamson were convicted in separate trials based partially on microscopic hair comparisons, done as part of a scientific testing method which has since been largely discredited. Fritz and Williamson were also convicted based on testimony of witness Glen Gore, an informant who was later proved through DNA testing to be the real killer. Gore has since been convicted of the rape and murder of Carter.

In 1988, Fritz and Williamson were convicted in separate trials based partially on microscopic hair comparisons, done as part of a scientific testing method which has since been largely discredited. Fritz and Williamson were also convicted based on testimony of witness Glen Gore, an informant who was later proved through DNA testing to be the real killer. Gore has since been convicted of the rape and murder of Carter.

Fritz received a sentence of life in prison, while Williamson was given the death penalty.

At one point, Williamson came within five days of execution before a court intervened.

If not for DNA evidence saved from the scene and later tested, Fritz might still be incarcerated for the rape and murder. Both he and Williamson were exonerated and released from an Oklahoma prison in 1999 based on the results of DNA testing. Fritz was incarcerated from 1988 to 1999, during a large part of his daughter’s childhood — time he can never get back. “That makes his story even more tragic,” said Pilate, who helped Fritz seek financial compensation for his wrongful incarceration.

“Dennis not only had to live through the horror of prison, but he also missed out on watching his daughter grow up.”

If not for DNA evidence saved from the scene and later tested, Fritz might still be incarcerated for the rape and murder. Both he and Williamson were exonerated and released from an Oklahoma prison in 1999 based on the results of DNA testing. Fritz was incarcerated from 1988 to 1999, during a large part of his daughter’s childhood — time he can never get back. “That makes his story even more tragic,” said Pilate, who helped Fritz seek financial compensation for his wrongful incarceration.

“Dennis not only had to live through the horror of prison, but he also missed out on watching his daughter grow up.”

For his part, Fritz is philosophical about his time in prison and the subsequent legal fight to gain his freedom and compensation. The publicity generated by the case helped focus attention on the wrongful incarceration issue.

“It made me feel like that if I had to go through this, there was some purpose,” said Fritz. In 2002, the City of Ada and the State of Oklahoma settled the lawsuits brought by Fritz and Williamson for significant amount, which cannot be disclosed because of a confidentiality agreement.

Fritz has remained active with the Innocence Movement in Kansas City, helping the Midwestern Innocence Project with fund-raising projects and keeping in touch with other local exonerees who are readjusting to society.

“It made me feel like that if I had to go through this, there was some purpose,” said Fritz. In 2002, the City of Ada and the State of Oklahoma settled the lawsuits brought by Fritz and Williamson for significant amount, which cannot be disclosed because of a confidentiality agreement.

Fritz has remained active with the Innocence Movement in Kansas City, helping the Midwestern Innocence Project with fund-raising projects and keeping in touch with other local exonerees who are readjusting to society.

Williamson has not fared as well, however. Upon his release in 1999, he continued to experience mental health problems.

Once an aspiring baseball player, Williamson deteriorated dramatically in prison and was moved to an Oklahoma psychiatric hospital. Sadly, in 2004, Williamson passed away. “I cannot think of two better examples of why it is important to allow inmates with provable, justifiable claims of innocence to have their day in court,” said Pilate. “Science has progressed to a point where if physical evidence still exists in cases that are five, ten, 15 years old, the key to proving actual innocence is likely at the justice system’s fingertips.

We need to make the appeals process easier for those inmates who can legitimately claim innocence through previously unavailable scientific evidence or testimony from witnesses who may not have been brought to the attention of the court during trial.”

Source Midwestern Innocence Project

.jpg)